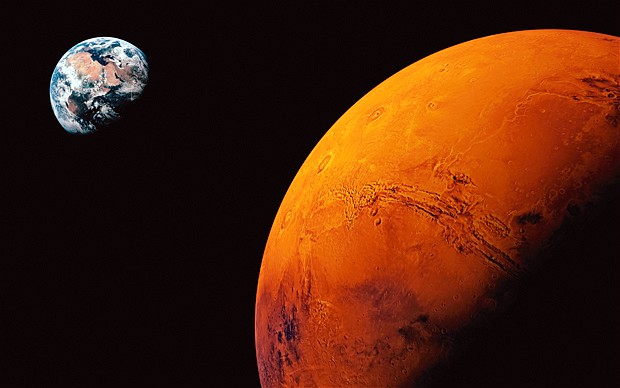

If Mars has methane, does it mean there’s life on the red planet?

08/25/2019 / By Edsel Cook

A recent study by European researchers strengthened the case for seasonal spikes of methane in Mars. First discovered by NASA’s Curiosity rover in 2013, the latest methane spikes were confirmed by orbiting spacecraft.

In 2019, Curiosity discovered that the methane levels in the Martian atmosphere changed from season to season. The gas hit its peak during the summer months in the northern hemisphere.

The rover also recorded two methane plumes within the massive Gale Crater. The first spike took place during June 2013 while the second one lasted from late 2013 to early 2014.

Researchers from Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) and their European counterparts presented evidence supporting the June 2013 discovery made by Curiosity. Their data came from the Mars Express spacecraft operated by the European Space Agency (ESA).

“While previous observations, including that of Curiosity, have been debated, this first independent confirmation of a methane spike increases confidence in the detections,” explained INAF researcher Marco Giuranna.

Furthermore, his team identified a location more than 300 miles (500 km) east of Gale Crater as the likeliest origin of the methane plume.

These findings have intrigued scientists, because methane is a possible biosignature.

While many geological activities release methane, most of the gas on Earth comes from living organisms. Some researchers believe that the methane on Mars comes from bacteria.

(Related: Satellite images of Mars show valleys and trenches where ancient rivers once flowed.)

European spacecraft confirms Curiosity’s detection of methane plume on Mars

Mars Express arrived at the Red Planet in December 2003. A year later, the ESA orbiter picked up methane in the Martian atmosphere.

The lead investigator of the European research team, Giuranna set out to cooperate with his NASA counterparts. When Curiosity landed inside Gale on August 2012, Giuranna tasked the orbiting Mars Express to scan the skies over the NASA rover.

The Martian atmosphere only contains small amounts of methane. The gas does not absorb light very well, making it hard to pick up with a light-based spectrometer from orbit.

Giuranna’s team came up with a different method of going over data collected by the spectrometer. They used the method on scans of Gale Crater during the first 20 months of Curiosity’s stay on Mars.

They hit the jackpot on June 15, 2013, when Curiosity sniffed a methane spike of six parts per billion (ppb) in the Gale Crater. The next day, Mars Explorer picked up a peak of 15.5 ppb in the air over the rover.

Methane might be trapped beneath Martian ice and escape during warmer seasons

To locate the specific region where the methane plume came from, Giuranna and his colleagues first organized the area around Gale Crater into square grids with an individual grid measuring 155 miles on each side.

Next, they ran a million simulations of methane plume scenarios for each grid. The computer models let them appraise the likelihood of a grid producing the gas detected by Curiosity and Mars Express.

Also, the researchers evaluated the geological characteristics of every square. They sought out fault lines, fault intersections, and other terrain features that might be responsible for the methane emissions.

“Remarkably, we saw that the atmospheric simulation and geological assessment, performed independently of each other, suggested the same region of provenance of the methane, which is situated about 500 km east of Gale,” Giuranna explained. “This is very exciting and largely unexpected.”

He added that the candidate region might feature a layer of ice that confined the methane beneath it. Giuranna offered several possibilities for the seasonal release of the gas.

For example, Martian ice might partially melt when temperatures rose during the northern summer season. The resulting faults in the permafrost allowed methane to escape.

Stay up-to-date with the latest on finding evidence of life on Mars at Breakthrough.news.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: alien life, astronomy, bacteria, breakthrough, Chemistry, Curiosity Rover, discoveries, Life on Mars, Mars, Methane, methane gas, outer space, research, space exploration, space research

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 CHEMISTRY NEWS